DNA to RNA : RNA Splicing

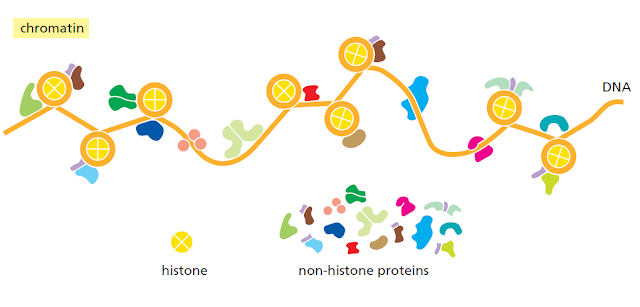

Although it may seem at first counterintuitive, the way a gene is packaged into

chromatin can affect how the RNA transcript of that gene is ultimately spliced.

Nucleosomes tend to be positioned over exons (which are, on average, close to the

length of DNA in a nucleosome), and it has been proposed that these act as “speed

bumps,” allowing the proteins responsible for exon definition to assemble on the

RNA as it emerges from the polymerase. In addition, changes in chromatin structure

are used to alter splicing patterns. There are two ways this can happen. First,

because splicing and transcription are coupled, the rate at which RNA polymerase

moves along DNA can affect RNA splicing. For example, if polymerase is moving

slowly, exon skipping (see Figure 6–30A) is minimized: assembly of the initial

spliceosome may be complete before an alternative choice of splice site even

emerges from the RNA polymerase. The nucleosomes in condensed chromatin

can cause polymerase to pause; the pattern of pauses in turn affects the extent of

RNA exposed at any given time to the splicing machinery.

RNA Splicing Shows Remarkable Plasticity

We have seen that the choice of splice sites depends on such features of the premRNAtranscript as the strength of the three signals on the RNA (the 5ʹ and 3ʹ splice

junctions and the branch point) for the splicing machinery, the co-transcriptional

assembly of the spliceosome, chromatin structure, and the “bookkeeping” that

underlies exon definition. We do not know exactly how accurate splicing normally

is because, as we see later, there are several quality control systems that rapidly

destroy mRNAs whose splicing goes awry. However, we do know that, compared

with other steps in gene expression, splicing is unusually flexible.

.png)

0 komentar: